By Suzanne Sparrow Watson

While my brother’s post last week was about his adorable grandchildren (and, yes, they are that cute and talented!), I was drawn back three generations to do more research on our great-grandfather, John Hoever (pronounced “Hoover”). My interest in him was renewed last week when I read an article originally published in the Napa Valley Marketplace magazine about the history of the Napa State Hospital. In 1900 John Hoever died there for reasons yet to be discovered. Napa was no ordinary hospital; it was more commonly known as the Napa State Asylum for the Insane. Well…that goes a long way in explaining our family peculiarities. Like many of you, I have passed by the hospital on my way through wine country, but never knew its history…or how dangerous it is today.

While my brother’s post last week was about his adorable grandchildren (and, yes, they are that cute and talented!), I was drawn back three generations to do more research on our great-grandfather, John Hoever (pronounced “Hoover”). My interest in him was renewed last week when I read an article originally published in the Napa Valley Marketplace magazine about the history of the Napa State Hospital. In 1900 John Hoever died there for reasons yet to be discovered. Napa was no ordinary hospital; it was more commonly known as the Napa State Asylum for the Insane. Well…that goes a long way in explaining our family peculiarities. Like many of you, I have passed by the hospital on my way through wine country, but never knew its history…or how dangerous it is today.

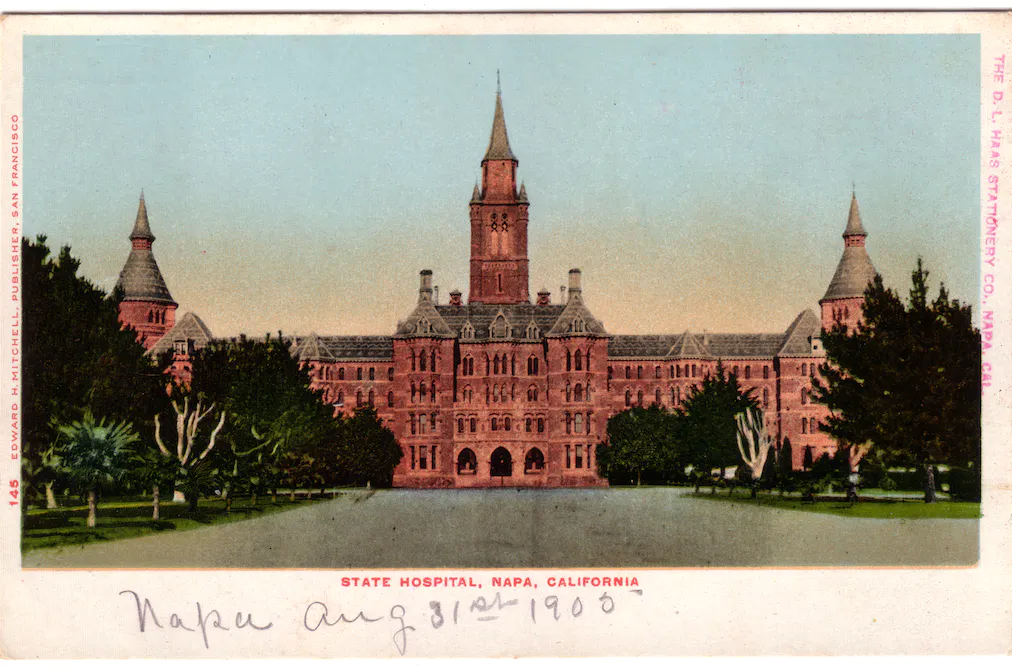

The hospital was opened on November 15, 1875. The original main building known as “the Castle” was an ornate and imposing brick building. By the early 1890s, the facility had over 1,300 patients which was more than double the original capacity it was designed to house. A majority of the patients were foreign born, like my grandfather. He left Germany in 1875 and immigrated to San Francisco.

The Napa Asylum treated patients for a variety of ailments; many of the early residents were admitted due to alcoholism or homelessness. This was a time in Europe known as “The Long Depression” when many people immigrated to the United States in search of a better life. But the U.S. was also in an economic downturn, so one can speculate that some of the immigrants ended up without work and homeless. Women admitted at the end of the 19th century were often diagnosed with acute mania, melancholia, or paranoia. The hospital treated everything from epilepsy, paralysis, and syphilis, to jealousy, masturbation, and even disappointment in love. Pretty much covered the gamut of social ills of the time.

In the early years of the hospital, work therapy was used as a common treatment for patients. The routine and predictability of asylum life were thought to aid patients. The grounds contained a large farm that included dairy and poultry ranches, vegetable garden, and fruit orchards that provided a large part of the food supply consumed by the residents. Growing their own food and using patients for labor also kept the costs down – and the profits up – for the directors of the hospital.

Over the years this bucolic site changed, as did the residents. Up until the 1920’s, patients were either self-admitted or sent there by their families. Slowly, as psychiatric care became more sophisticated, many of the ailments that confined people to the hospital were able to be treated on an outpatient basis. The facility was re-named, Napa State Hospital, and served as a traditional psychiatric hospital until the 1990s when it started taking court referrals. Despite being filled with perpetrators of violent, often heinous crimes, it was still considered to be a hospital, not a prison. The patients were committed, but not locked up. Police officers were posted at hospital entrances, but uniformed guards did not patrol the halls of even the highest-risk units. So, over time the most violent patients were left to terrorize the others freely, with only doctors and nurses to stop them. In 2010, a nurse was murdered by an inmate, which prompted the hospital to hire more police officers and the staff were outfitted with personal alarms so they could call for help if they felt threatened. So, today it is safer, but about 90 percent of the patient population is funneled into the hospital through the criminal justice system. I don’t think Napa State Hospital is going to make anybody’s “Top Ten Places to Work” list, no matter how many improvements they make.

As for our great-grandfather, I still have no idea why he was committed to Napa. Perhaps my great-grandmother, Annie, kept the reasons to herself, as neither my grandmother or father ever indicated they knew anything about his time there or manner of death. In the July 1900 census, he was listed as having been in Napa Hospital for 12 months. Annie gave birth to a daughter in February 1900, so he must have gone in shortly after she found herself pregnant. He died in September of that year and his obituary said that “his funeral had the largest crowd ever seen in town, which bore testimony to the esteem with which this good man was held.” So, I don’t think he had been the town drunk.

As for Annie, she was a remarkable woman for her age and time. After John’s death she took over managing the jewelry store they owned and was described in “The History of Colusa and Glenn Counties” as someone who had “demonstrated her ability as a businesswoman and won great success through her own efforts”. That was quite a compliment to be given a woman in business in 1918! I have inherited the diamond from her engagement ring and whenever I think I’m having a hard time I look at it and know that I have it easy compared to her.

I’m not sure I’ll ever find out why John was committed to Napa. Several years ago I wrote the hospital asking if they had any records of him, but I never heard back. Now that I know more about the current situation, I think the staff has enough on their hands just to stay alive without having to answer emails about someone who died in 1900. All I know is I will never pass that hospital again without thinking about him and vowing that if I’m ever up on a violent crime charge, I’ll plead guilty rather than risk going to Napa!